If you frequented the late All Sports Stadium to watch the Oklahoma City 89ers Triple A baseball team play during the 1980s, you probably were a fan of an animated scoreboard feature known as the Dot Race.

I know I was.

I can remember many nights at the ballpark when the Dot Race prompted thousands of fans to cheer on their favorite computerized, pixelated “Dot” like they were at Churchill Downs. Sometimes, there seemed to be more excitement surrounding the faux scoreboard race than the actual game.

If you can recall through the hazy years of the past, the three Dots — labeled Dots 1, 2 & 3 — raced down an animated speedway toward the finish line. Sometimes a dot veered into the wall or had a breakdown just when it appeared it would win the race.

A form of the Dot Race lives on in the 2020s as between-inning entertainment for the Texas Rangers and other Major League parks around the country. And as time has passed, few people recall that the Dot Race had its beginning as humble, white dots on the 89ers scoreboard in Oklahoma City.

Turns out, the Dot Race was the brainstorm of a then part-time 89ers employee and University of Oklahoma student named Larry Newman.

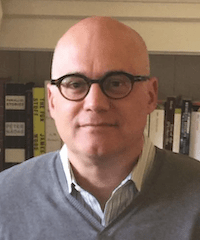

By coincidence, when I arrived in The Oklahoman newsroom as a sports copy editor in 1983, Larry also worked part-time at night on the paper’s sports desk, taking scores and writing up short summaries of high school basketball and football games.

I got to know him as a bright, competent young man who also had an interest in computers and software coding. One night he brought the first Macintosh computer I had ever seen in the wild into the newsroom.

So, it wasn’t long before I learned that Larry was the creator of the Dot Race, although I didn’t know the full story until a recent Saturday morning when we caught up with one another at MentaliTEA and Coffee in Bethany. It was the first time we had seen one another in roughly 40 years.

I wanted to know the story of the Dot Race, and Larry was happy to share it.

Larry Newman began working as a ticket taker for the 89ers while in high school back in the late 1970s. He eventually was asked by owners Bing Hampton and Patty Cox to take over duties of operating the scoreboard pitch count from the press box.

“I did balls and strikes for probably two or three years,” Larry said. “In that role, you are watching every single pitch of every single game throughout a baseball season. So, a lot of innings.”

The next development leading to the Dot Race involved a new scoreboard installed at All Sports Stadium in a sweetheart deal between the 89ers, the City of Oklahoma City and the Miller Brewing Co.

“The people from Miller said we will give you a brand new scoreboard and attached message center in exchange for leaving the Miller Brewing Company logo advertisement on top of the new scoreboard for some number of seasons,” he said. “That’s what the Dot Race ran on; that message center.”

That brand new scoreboard offered a three-line message center, which provided the opportunity to not only display text, but to develop simple graphics that would be displayed. It came with a couple pre-made animations that had clapping hands and home run celebrations.

So, Larry learned to do frame-by-frame animations that were written in code to magnetic tape storage — no fancy floppy discs for this scoreboard. Larry began working on his Dot Race idea because the 89ers had no between-inning entertainment during one half inning of each game.

Larry dove into the coding challenge. He said it took about 35-40 hours to create the first race course and the dots — “pixel by pixel,” but after the first one was completed, programming each individual race to run on his course took about 30 minutes a night, he said.

So, the Dot Race was born.

“When I showed the idea to 89er owners Bing Hampton and Patty Cox, they approved the idea and actually promoted it at each 89er home game,” Larry said. “The public address announcer said, ‘hey, we’ve got a new feature, the Dot Race. Pick your winning Dot.’ We did it every night and people started getting into it.”

Larry programmed a new Dot Race for every game, and fans liked it so much that some asked him to tell them in advance what the winning Dot was going to be that night. He said he never disclosed the winner prior to any race.

“I had a race once where a Dot ran into the wall and an ambulance came out and picked it up,” he said. “That one took a lot of time to build.”

During this time the 89ers switched Major League affiliation from the Philadelphia Phillies to the Rangers, which was critical to the eventual spread of the Dot Race across baseball.

One night, visiting Texas Rangers officials that included then-General Manager Tom Grieve came to OKC to watch their minor league players. The Rangers reps spoke to Larry in the press box that night.

“They came up to me and said, ‘hey we want to see this Dot Race thing; we’ve heard about it from a couple of the players,’ ” Larry recalled.

The Rangers officials watched it and saw the fans reacting to it.

“They asked, ‘how did you do that?’ I said ‘it’s a very involved process.’ “

A short time later, he got a call from the Rangers scoreboard operator. The Texas version of the Dot Race was soon born and became hugely popular.

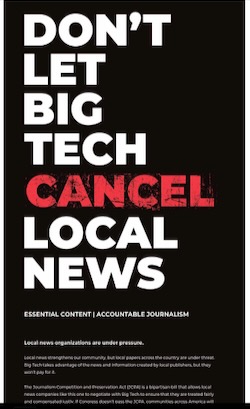

The 89ers — but not its inventor — got credit in early DFW area newspaper articles about the Dot Race phenomenon.

A story in the August 24, 1986, edition of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram quotes Rangers PA announcer Chuck Morgan as crediting the idea to the 89ers, but said it came to the Rangers via a newspaper reporter.

A story in the August 24, 1986, edition of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram quotes Rangers PA announcer Chuck Morgan as crediting the idea to the 89ers, but said it came to the Rangers via a newspaper reporter.

But in newspaper articles about the Rangers Dot Race just a decade later, Morgan made no mention of its Oklahoma City roots.

And on the current Website called “Ballpark Brothers,” the Dot Race is 100 percent attributed to Morgan.

“The Dot Race at Arlington Stadium was first originated by Arlington Stadium announcer Chuck Morgan, who somehow got the tech guys to have 3 colored dots circle around an oval on the scoreboard, much to the fans’ glee. It was this dot race that spawned all other video races and the human races in ballparks across North America.”

I guess you can chalk that up to the loss of institutional memory over time.

So, I asked Larry if he was bitter at not receiving any recognition for creating the Dot Race phenomenon that continues to circle scoreboards in different forms around the nation.

“It didn’t upset me, but I do remember walking into the Rangers stadium not too long after they came to Oklahoma City,” Larry said. “They were handing out a small card with a dot color on it to everyone entering the stadium. Some of the cards had a red dot, some had a blue dot and some had a green dot, and it was sponsored by Wendy’s or Arby’s or someone. If the dot you were handed won the race that night, you could go to the restaurant and get a free small burger or something.

“I’m like, ‘these people are finding a way to make money off my Dot Race.’ ”

But decades have passed, and Larry Newman is now a retired technical writer whose last employers were tech giants Google and Oracle. He looks back over the years and finds the silver lining in the story.

“I’m happy that people have enjoyed it for so many years,” he said. “Absolutely.”

In the grand scheme of Dot Race life, that’s a winner.

EDITOR’S NOTE: More info on the roots of the legendary Dot Race:

Larry Newman told me the Dot Race got a big boost with the 89ers audience when 89ers Director of Communications Monty Clegg began doing play-by-play announcing of the racing dots. I contacted Monty, who now lives in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, to get his side of the story and here’s what he told me:

“Larry was really creative and worked some magic with a limited slate of a three-line message center with the 89ers,” Monty said. “Bing Hampton suggested that we have a Dot Race track announcer. Since I worked in the press box, I think I was volunteered. I still remember that as the dots rounded for home, I would always say ‘And they’re spinning out of the final turn!’

The Dot Race tale is a great story, and I thank Larry Newman and Monty Clegg for letting me share it.