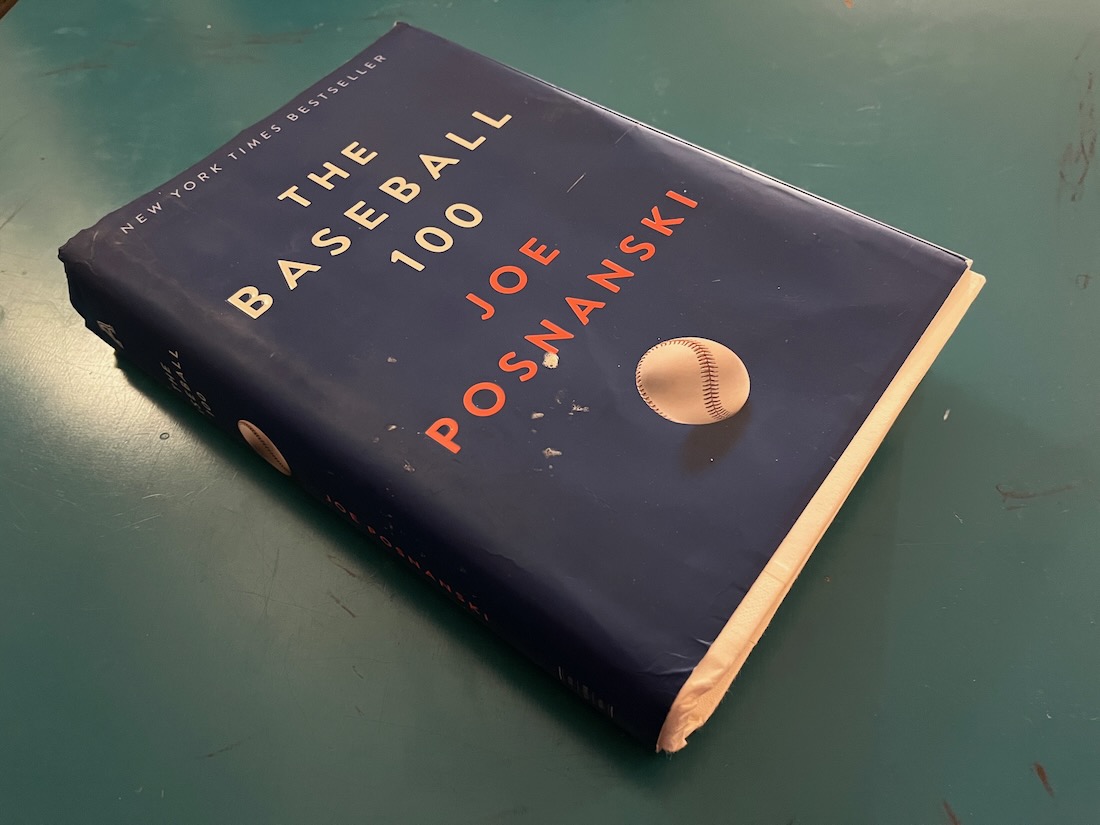

For the past five months, I’ve walked around our house carrying a massive tome that resembles those old giant-sized King James Bibles that are cherished possessions of many families.

Only this Good Book is titled The Baseball 100 (2021, The Athletic Media Co.) and written by long-time baseball writer Joe Posnanski. It was a birthday gift last April from my friend Ed Godfrey.

Thank you, Ed.

If you’re not familiar with Posnanski, he made his reputation as the baseball beat writer for the Kansas City Star newspaper before moving on to Sports Illustrated, NBC Sports and The Athletic, among his credits. Today, he’s publishing his prose on his own blog at JoeBlogs.

More about Posnanski’s background here.

It’s obvious that Posnanski’s first love is baseball, and, in fact, his latest best seller in a long line of bestsellers is entitled ‘Why We Love Baseball.’

Anyway, back to The Baseball 100. I read it slowly and savored each individual profile of what Posnanski considers to be the best 100 players in Major League history. When I first opened the book, I flipped hurriedly through the pages until I found the Nolan Ryan chapter, just to make sure Posnanski included Big Tex.

Ryan came in at No. 50, and the logic of that ranking was that about half the baseball world (me included) thinks he’s one of the top pitchers ever, while the other half sees him as vastly overrated.

So, then I went back to the beginning and read the book through. What struck me was how often father-son dynamics played into the development and character of so many players.

For instance, let’s consider Oklahoma native Mickey Mantle. Mantle’s father, Mutt, began pitching to him at their Commerce home when the Mick was 6 years old, making him bat from both sides of the plate. Mickey didn’t exactly want to be a switch hitter and wasn’t certain he wanted to be a baseball player from the start.

But his dad willed it even before he was born.

“Mutt knew with a chilling certainty that his future son would be called Mickey, after his favorite ballplayer, Mickey Cochrane, and that Mickey Mantle would be the best ballplayer of them all,” Posnanski writes.

Mickey Mantle did turn out to be one of the great all-time Major League players. He was the All American boy who led the New York Yankees to seven World Series titles in 12 appearances from 1951 to 1964.

Ranked No. 11 all-time by Posnanski, Mantle also was an alcoholic who cheated on his wife and was mostly absent from the lives of his children. I’m pretty sure Mutt’s obsession shaped Mickey beyond baseball.

You learn how flawed so many of our heroes were in The Baseball 100, from Mantle to Pete Rose to Ted Williams to Barry Bonds to Roger Clemens. The Baseball 100 also shares stories about baseball heroes who were model citizens, like Ozzie Smith, Stan ‘The Man’ Musial, Derek Jeter, Albert Pujols and Brooks Robinson, to name a few.

But the theme of overbearing fathers came up again and again. Consider George Brett, who is a contemporary hero to those of us of a certain age and who comes in at No. 35 in Posnanski’s rankings.

“Fear drove George Brett,” Posnanski writes. “His father, Jack, made sure of that.”

No matter how well Brett played or what amazing stats he put up for the Kansas City Royals, it was never good enough for his father. Never.

In fact, on the night before Jack Brett died of cancer, he spoke to George on the phone and asked him how he did that day. George told him he went 0-for-4. “Well, did you at least hit the ball hard?” his dad asked. “I did, Dad,” George lied to his dying father. “I hit it hard.”

Brett had struck out three times that day.

Then there is Pete Rose at No. 60. We all know how his story played out, the betting on baseball, the relentless chase of the hits record, the womanizing, the Charlie Hustle reputation.

What Posnanski tells us is that Pete’s father, Harry “Big Pete” Rose never gave him the opportunity to develop as a person. Big Pete saw him as a Major League star, and turned him into a switch hitter at 8 years of age. He even demanded that his Little League coach let him switch hit.

It’s the Mickey Mantle story playing out all over again in Cincinnati, Ohio. Except Pete Rose was banned from baseball for life for betting on the game he loved.

And then there was Ted Williams, an all-time player and war hero who fought fans, the media and his own demons. Posnanski doesn’t write about an obsessive father in his life — he barely knew his father — but does quote Williams’ own daughter who said that her father was mentally ill.

“My father was sick,” Bobby Jo (Williams) said. “And it’s a damn shame that, because he was Ted Williams and because nobody wanted to tell him like it was, including myself, he suffered and progressively became more ill by the years.”

In addition to father-son relationships, there is another major theme that runs through the book.

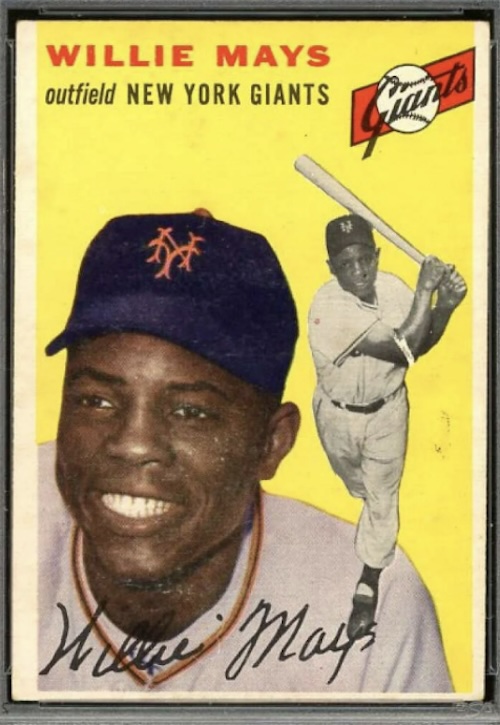

Posnanski writes extensively about the plight of African American stars who never got the chance to play in the Major Leagues. For decades. they were forced to play in the largely invisible (to the white audience) Negro Leagues. Their stories come to life in The Baseball 100, as well.

So, who does Posnanski rank as the No. 1 player of all time? I’ll leave it to you to get a copy of this outstanding book and find out for yourself.

Hint: Say Hey when you finally figure it out

Read The Baseball 100 and savor the stories of the heroes of our youth.